From airbags to speed reductions, these are the safety measures the Tour is studying to implement

Although this Tour de France 2023 is not being particularly eventful thanks to its selective route, a UCI study indicates that crashes have increased in the last 5 years having grown in the last season the worrying figure of 24%. The director of the Tour de France, Christian Prudhomme, has promised to take measures to reduce the number of accidents.

How to make the Tour de France safer for cyclists?

The safety of the cyclists is one of the recurring themes within the peloton and one of the battle horses of the representatives of the professionals against the race organizers who often put the peloton in a real trap. Nor is the UCI free of blame, more concerned on many occasions with measuring the height of the socks and prohibiting positions that have not caused any problems than with actually controlling that the routes offer full guarantees.

The controversy about the dangerousness of the routes was reignited just before the start of the Tour de France after the sad death of Gino Mäder in the queen stage of the Tour de Suisse after a finish descending the last pass of the day towards the finish line in which the riders exceeded 100 km/h. A debate that, once the Tour de France began, did not diminish after the eventful start with the withdrawals of Richard Carapaz and Enric Mas in the first stage with start and finish in Bilbao. And surely, we will talk about it again next weekend when the day of the Gallic round concludes in such a classic finish as Morzine, which always involves facing the technical and fast descent of Joux Plane.

Updating the regulations

RECOMENDADO

Alcoholic beverages with the fewest calories

What would you do if you won the lottery? This cyclist bought himself a €20,000 bike

Tips for cycling in the rain

25 cycling gifts ideas to get it right

When do helmets have to be changed? Do they have an expiration date?

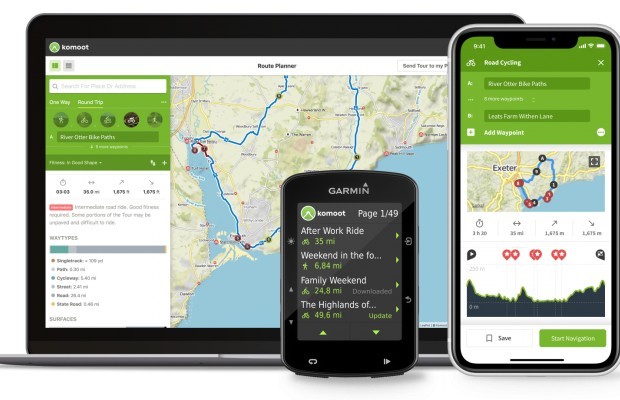

The best apps for cycling and mountain biking

From the side of the cyclists' representatives, they advocate for a regulatory framework to ensure that certain safety criteria are met in races. Therefore, the first thing they ask for is to be listened to in order to be able to transmit the multitude of ideas that arise among them, the only ones who know 100% of the risks they take on each day of competition.

As an illustration of the improvement of safety conditions, they give the example of the world of Formula 1 where it has evolved since the 90's when we saw truly terrifying accidents such as the one that took the life of the legendary Ayrton Senna. For example, a few days ago, the Israel-PremiertTech cyclist commented in a statement that "we need more safety equipment and the bikes have to go slower", with this the Canadian opened another front putting the focus not on the routes but on the current bikes, increasingly faster thanks to aerodynamic gains or the use of wider tyres pointing out these points as aspects in which to reduce the speed of the bikes.

Others like Matteo Jorgenson put the focus on the aforementioned downhill finishes "we are riders and if you put a goal at the end of a downhill we are going to ride it as hard as we can to try to win, which is a bit dangerous". However, on this point, UCI president David Lappartient was clear on the matter "if we started by vetoing the final descents, why not veto the mid-race ones as well? That's not competition.

Improving the protection

Some have even suggested that the cyclist's protective equipment should be improved, since currently only a helmet is mandatory, and some even talk about some kind of airbag system. The problem is that the cyclist is completely exposed to abrasions and impacts at high speed and only his head has the protection of the helmet which, on the other hand, has prevented certain crashes from ending in tragedy, such as the famous crash of the ill-fated Fabio Casartelli that shocked us all in the 1995 Tour de France and was the trigger for the debate that led to the current mandatory use of helmets.

Evidently these types of systems, already implemented in some existing solutions for urban cycling, could be a good way to improve.

Also referring to the routes, the UCI study we mentioned at the beginning mentions that most of the accidents occur in urban areas. Precisely that is traditionally the greatest fear of cyclists competing in the Tour de France. The small French towns are a trap of narrow streets, traffic islands, traffic circles, many traffic circles; and all kinds of solutions to reduce the speed of cars on the streets that are not too compatible with a peloton riding at 60 km/h.

The challenge for the organizers is to strike a balance between the safety of the routes and their continued attractiveness. It would be much easier to organize the finishes in the middle of a shopping mall parking lot on the outskirts of a city or to move the public dozens of meters away from their idols, but that would take away much of the closeness and essence of the sport.

An aspect in which the big organizations such as the Tour de France have been improving, signaling and marking each obstacle much better or adding protections such as mats in the most critical places. After Gino Mäder's accident, the Tour of Switzerland promised to install new signs and warnings at the more than 5,000 dangerous points identified on this year's route.

In any case, we must not forget that cycling is a sport that is practiced on a device weighing little more than 7 kilos whose only contact with the road are two small rubber areas and on which it is possible to reach frightening speeds. It must be assumed that there will always be some risk, although this does not detract from the need to continue to identify them and seek solutions to reduce the risks.