Intermittent fasting may increase risk of premature death

A recent study from the University of Tennessee associates a higher risk of mortality with those who eat only one meal a day. The researchers analysed data from more than 24,000 people between 1999 and 2014. Despite the results, they warn that this relationship "does not imply causality", although it does "make metabolic sense".

Intermittent fasting, on everyone's lips

Among the countless diets or eating habits (as it is probably more correct to refer to it) that exist, intermittent fasting is perhaps one of the best known. Many famous and not so famous people have jumped on the intermittent fasting bandwagon in recent times.

Supporters claim that intermittent fasting has great health benefits for our bodies. Now, a study published in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics warns that it may increase mortality.

RECOMENDADO

Tips for cycling in the rain

25 cycling gifts ideas to get it right

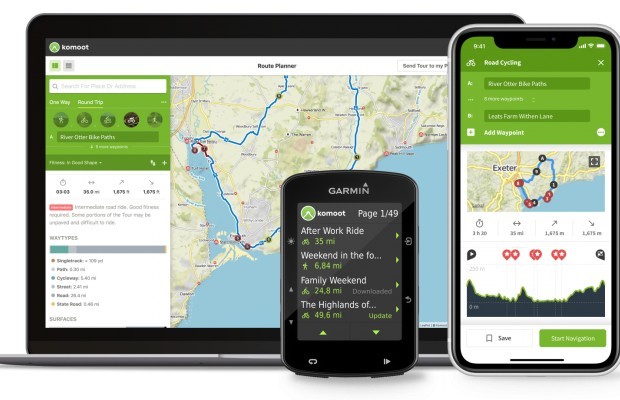

The best apps for cycling and mountain biking

Black Friday 2025 cycling bargains: save on Garmin, POC, Maxxis and more

Black Friday Garmin 2025: the ultimate guide to choosing your GPS at the best price

How to wash your cycling clothes? 10 keys to make them always look new

Nutrition is a constantly changing science. In fact, one of the study's researchers, Wei Bao, explains that the "findings are based on observations drawn from publicly available data and do not imply causality. However, what we observe makes metabolic sense."

The popularity of intermittent fasting as a "solution for weight loss, metabolic health and disease prevention" makes the research relevant "to the large segment of American adults who eat fewer than three meals a day," according to lead author Yangbo Sun.

What the study states

In particular, the results show that skipping breakfast is associated with an increased risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease.

For their part, skipping lunch or dinner is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality, a risk that even people who eat three meals a day but eat "two meals less than 4.5 hours apart in a row" also have.

The research is limited to adults over the age of 40. The results have been extracted after analysing the case of more than 24,000 people who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 1999 and 2014.

As mentioned, the authors do not conclude that there is causality, but they do reflect that their results "make metabolic sense". In this regard, Dr Bao explains that skipping meals often "means ingesting a greater energy load at the same time, which can exacerbate the burden of glucose metabolism regulation and lead to subsequent metabolic deterioration".

Furthermore, Dr Bao adds that "this may also explain the association between a shorter meal interval and mortality, as a shorter time between meals would result in a higher energy load in the given period".

Sun concludes by stating that "based on these findings, we recommend eating at least two or three meals spread throughout the day". Therefore, always consult a specialist first.