What is the pavé and why cyclists love it so much?

Pavé, a word derived from the French, refers to the paving that covers trails and roads. A surface once much more common in fields and cities that with the advance of the twentieth century made way for the more versatile asphalt. However, for the cyclist it is still associated with epic races and cycling of other times. The spring classics, throughout the months of March and April, mainly on Belgian soil, although Paris-Roubaix is the main event, keep the spirit of these races of the past alive year after year.

Stones loaded with history: the pavé's past

The pavé is a road made of cobblestones. Like the ancient Roman roads, the blocks of solid stone follow one another, forming a marvelous puzzle of geometric figures. This romantic image contrasts with its hardness: cycling on pavé is very demanding and cycling at a good pace and without risks is only available to those with a refined technique on this surface.

RECOMENDADO

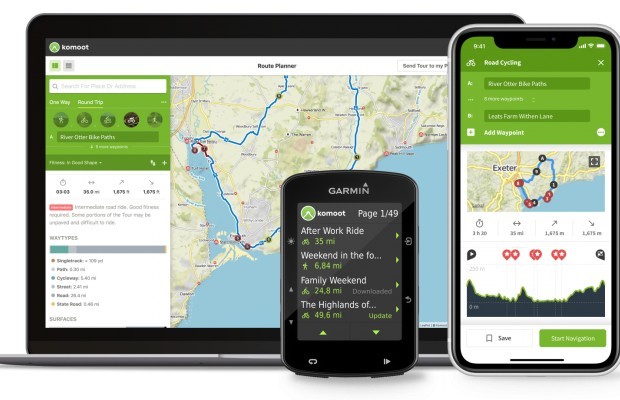

The best apps for cycling and mountain biking

Black Friday Garmin 2025: the ultimate guide to choosing your GPS at the best price

How to wash your cycling clothes? 10 keys to make them always look new

Cycling can help you fight the effects of the time switch

Easy to apply tips for riding faster

The real importance of signing up for a race

Before the mid-twentieth century, roads and streets in cities were paved to facilitate their maintenance and transit before the passage of carts and horses, the only vehicles available, until the first cars appeared at the end of the nineteenth century, almost at the same time that the bicycle began to become a popular means of transportation.

This hard and resistant surface was especially necessary in places where rain was frequent and turned roads into muddy, inaccessible areas. This is why it is an image that we associate much more with northern Europe, although it was also a common surface in southern cities.

The generalization of the use of cars and the discomfort that cobblestones added to vehicles circulating at higher and higher speeds made it necessary to look for other types of pavements, resorting over the years more and more to asphalt, which gradually buried the pavement under a layer of tarmac.

Cycling races, which began to be held in parallel to the construction of the first safety bicycles, the name given at the end of the 19th century to bicycles as we know them today, with two wheels of equal size, chain drivetrain, etc. as opposed to the bulky velocipedes with their gigantic front wheels. Races were held on the roads that existed at that time, regardless of whether there was dirt under the wheels, the most common, or cobblestones.

From these times date races that still remain on the calendar today, such as Paris-Roubaix, whose first edition was held in 1896; Liège-Bastogne-Liège, known as the dean, dating back to 1892, or Milan-Turin, the oldest race on the calendar, which began to be held in 1876. As the 20th century progressed, these races left us in the photographic records a large part of the iconography that we now associate with these races.

However, as we said before, asphalt gradually gained ground over cobblestones, the latter being more and more forgotten except in the Flemish lands where its cobblestone roads, which are the backbone of the communications between the vast rural areas of Flanders, of a dispersed urbanism, continued to be used and maintained.

The Paris-Roubaix, which had put cyclists covered in mud as they pedaled over irregular stretches of rural roads paved with cobblestones, gradually declined and became a bland flat race with the disappearance of these stretches and the constant changes in the route. Until 1968, when the race organizers decided to redesign the route, looking for secondary roads and rural roads, when the mythical Arenberg forest was discovered, perhaps the most mythical cobblestone section in cycling.

The campaign to save the essence of this event began with the collection of signatures to preserve the cobblestone roads, the organization of cyclotourism events and, in 1982, the birth of Les Amis de Paris-Roubaix, an association dedicated since then to safeguarding the cobblestone sections on which the event takes place and which are revised and repaired year after year by its members.

A very particular surface and that nowadays causes speculation and mixed opinions every time it is introduced in a race, especially if this race is the Tour de France that every so often traces a stage through these sections, as we could enjoy in the 5th stage of the Tour de France 2022 and that gave us a tremendous show with the offensive of Tadej Pogacar, the crash of Primoz Rogliz or the fierce defense of its leaders by Wout Van Aert.

The peculiarities of pedaling on pavé

Riding on pavé is something atypical and forces the cyclist to apply a specific technique when pedaling in order to move forward in the most efficient way. Besides, it is not risk-free when we do it on a road bike where the chances of suffering a flat tyre or a crash increase. Not to mention if the rain makes its appearance and turns the cobbles into a muddy surface on which keeping your balance becomes a real art.

When pedaling on cobblestones, the bike itself plays an important role in the first place. Current models increasingly accept larger tyres, the air volume being the first line of defense against the continuous impacts to which we are subjected on the cobblestones. In addition, brands have been developing specific models of road bikes in order to face a race like Paris-Roubaix with the best guarantees.

Back in the 1980s we could already see bikes with disproportionate steering angles and wheelbases in order to find the best stability and absorption on the pavé. Today, this role is left for Gran Fondo style bikes, born with a cyclotourist orientation although, in the case of some firms such as Trek, Specialized or Cervélo, they are also authentic racing machines with more stable geometries and carbon laminates in which impact filtering is a priority.

The other half of pedaling effectively on cobblestones is rider technique, which is difficult to apply when riding on cobblestones and should be learned if you don't want to end up completely wrecked after just a few kilometers on this surface.

The ideal position for pedaling on the pavé is well seated on the saddle, if possible trying to delay the weight on the saddle to give more support to the rear wheel. We will try to maintain an agile but constant pedaling without abruptness, which sometimes helps to carry a sprocket less than we would usually use at a particular point but without being so hard as to lead to get stuck.

However, what really makes the difference is to choose the ideal pressure in our tyres so that we find the balance between a good ride on the road sections, sufficient absorption, grip and avoid that the impacts reach to damage our tyres. An aspect to which professional riders dedicate long days of testing during the weeks prior to the race and which is decisive in the final result.

On the long bikes with traditional geometry, riders chose to hold on to the horizontal part of the handlebars in order to be able to bend their elbows and thus achieve optimal absorption. With today's bikes, which have more compact dimensions, this image has become a thing of the past and riders remain gripped to the handlebars, but with increased elbow flexion to provide the necessary absorption.

The secret to avoid being crushed on the pavé is the grip on the handlebars. Whether on the horizontal part of the handlebars or on the levers, the hands must be loose, simply covering the contour to prevent the grip from slipping, but loose, allowing the handlebars to dance between them and the bike itself to find its own way over the rocks. The result is that, on a road bike without any kind of suspension, the impacts of the rocks will always have the upper hand, causing exhaustion of the arm muscles and we have even seen cyclists with the palms of their hands completely raw.

It is also important to choose the best route for the section. On the Paris-Roubaix cobblestones, rural roads usually used by tractors and other agricultural vehicles, the pavé gradually gives way to the passage of these vehicles, becoming buckled in the central part and completely destroyed in the center. This also occurs to a lesser extent on the Flemish sections, which are flatter but with the cobblestones in the rutted areas more deteriorated than elsewhere.

We must therefore be constantly attentive to the terrain to decide which area is in the best condition and react quickly to change our position on the road surface, from the center to the sides, taking advantage of the side flashings if they exist, anything goes as long as we do not lose momentum and leave the least amount of forces in the sections.

When the rain makes its appearance everything becomes much more "fun", having to add to all the above a touch and precise lines to avoid any kind of abruptness that leads us to the ground on a surface that becomes a real skating rink.

If we talk about Flanders, things change because, although there are also flat sections, the characteristic pavé is usually associated with the steep hills that mark the landscape where, in addition to the uneven terrain and less adherence of the cobblestones, there are slopes often over two digits. Maintaining traction becomes the most important thing, having to apply a technique that will be familiar to those who practice mountain biking and that consists of playing with the weight to maintain the balance between the rear wheel so that it does not lose grip with the impulses of our pedaling and, in turn, provide sufficient weight to the front to be able to choose the best line and prevent the front wheel from lifting and unbalancing us.

There is no halfway point on the cobblestones: you either love it or you hate it. In any case, pedaling through the rough sections of Roubaix or the steep walls of Flanders is a special experience that you can also enjoy by participating in the cyclotourist rides that, in the days before the professional races, go over these cobblestones on which a large part of the most epic pages of cycling history have been written.