Countersteering, braking and cornering: the basics to improve your cornering skills

Tracing curves optimally is a key skill for anyone looking to go as fast as possible on their road bike. Beyond giving us a few meters of advantage that, depending on the circumstances, can be decisive, it helps us save energy and gain safety on the bike.

Discover how to master your bike 100% in curves

On several occasions, we have talked about the importance of technique in road cycling and the usual neglect of it by those who practice this discipline, a neglect that is much more evident in amateur cyclists and cycle tourists who may even have a deficient bike handling.

When we talk about technique on the road bike, we often only think about descending mountain passes, but, however, crossing urban sections or simply navigating roundabouts at speed requires certain skills to do it quickly and safely, situations that have in common the ability to trace curves in the best possible way.

RECOMENDADO

What benefits does bicarbonate have for cyclists?

Is a cyclist born or made? The eternal debate between talent and training

What are the five monuments of cycling?

How much time would a professional cyclist take out on an amateur in a race?

Why do most cyclists wear their glasses outside their helmets?

What happens if you exceed your maximum heart rate? Risks of pushing yourself to the limit

Taking curves on a bike is a kind of art, a vehicle in which, unlike motorized ones, we do not have an engine brake to slow us down when we stop accelerating, nor do we have an engine that allows us to easily regain lost speed. Therefore, tracing curves becomes a balance game between losing the least possible speed that will later allow us to regain the rhythm with minimal energy expenditure, and knowing when and how much to brake to avoid overshooting, something that can lead to a fall.

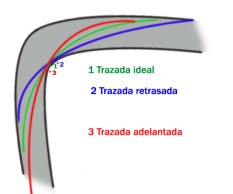

When it comes to taking curves, the first important aspect is, how could it be otherwise, the racing line. Here we must first define what the ideal racing line is, that is, the one that requires the least turning radius and maximizes the width of the road available in each situation, legally, no using the opposite lane or other infractions. The ideal racing line essentially involves starting on the outer edge of the road, braking to the entry point of the curve, and once there, releasing the brakes and gradually closing in towards the apex where we will start to straighten the bike and accelerate progressively to exit on the outside of the curve.

However, the ideal racing line is not always the optimal one. In many cases, it may be of interest to hold the bike back more to enter the curve a little later and be able to start accelerating earlier. In other situations, if the curve is linked to another, we may need to sacrifice opening up on the exit of the curve to stay on the inside and be able to take the second one correctly. Finally, we have the option of attacking the apex of the curve early by holding the bike back as little as possible, allowing us to be more aggressive. Different alternatives that, unfortunately for those expecting an answer telling them when to use one or the other, we can only decide which one to use based on our experience and the specific situation. There is no universal recipe.

What does not change is the methodology when facing the curve. Open up, brake to the entry, again experience and our skill will tell us how much, release the brakes and lean the bike to head towards the apex that we will look for with our eyes since, instinctively, we steer the bike where we look. Theory dictates that we should release the brake as soon as we start to lean the bike, but as skill improves and we seek to push further, a strong braking is done in a straight line but is maintained during the lean, gradually releasing it as we approach the apex. In this case, it is important to be very aware of the grip of our tires, an excess of braking while leaning, especially on the front wheel, means losing grip and, most likely, ending up on the ground. This is precisely what we see in races when risks are taken to push to the limit and gain tenths in each curve.

It is also important to note that it is not always necessary to brake in curves and one of the problems when it comes to being efficient for most cyclists is precisely that, braking excessively, which then results in a great expenditure of energy to regain lost speed. In many situations, a correct racing line, again something that needs to be practiced, allows us to avoid using the brake, even to stop pedaling. The pinnacle of this skill can be seen in fixed gear races, races with fixed gear bikes, without brakes, and in which pedaling cannot be stopped, sometimes held on twisty circuits where the racing line in curves is vital.

Speaking of grip, it is also important to play with body weight, which can be shifted forward or backward to give more grip to the corresponding wheel or lean towards the inside or outside of the curve depending on the available grip. For example, on wet surfaces, we will lean more towards the inside, allowing us to keep the bike straighter, avoiding the wet ground from causing us to lose grip on the tires.

Another necessary knowledge when tracing curves is mastering the bike's lean angle through the countersteering technique. We remind you that the bike, above a certain speed, leans due to the force we exert, often unconsciously, on the handlebars. If we turn the handlebars to the right, the bike leans to the left and vice versa. Knowing this effect, we have a tool that we can control consciously and that allows us to regulate the degree of the bike's lean.

There are many ways to improve our ability to take curves. The most brute, but effective, is following someone who traces better than us. Normally, if we have the correct tire pressure, another essential data for tracing curves as fast as possible and most people still use excessive pressures, is that if the cyclist ahead of us passes, we can also pass if we do exactly the same. Obviously, this is a somewhat radical method that can lead us to exceed our bike handling capabilities.

Before reaching that point, it may be helpful, as is done in cycling schools, to do cone circuits that allow us to gain bike handling skills. Simply, in a square or a large parking lot, place some cones, playing with separations and layouts, and gaining bike handling skills.

Practicing off-road cycling, whether gravel or mountain biking, is also an excellent aid when it comes to gaining confidence in curves and mastering the road bike as these disciplines involve terrain with less grip than asphalt, allowing us to explore the limits of the tires and, above all, learn to feel the grip losses and play on that fine line where they support us but slide in a controlled manner.

Of course, as was the case with descents, knowledge of the terrain is vital when tracing fast and, although we may always encounter surprises, in the end, we learn how to trace roundabouts according to the exit we are going to take, or how to take advantage of the width of the street in a 90-degree turn in the city since the variety of situations we end up encountering is not so great that we cannot end up mastering them.

Finally, there is the psychological factor. If we constantly go with fear thinking that we are going to fall in every curve, we will never be able to trace curves smoothly, and we may even accumulate tickets to fall by blocking ourselves in some situations.