"You can wear whatever you want, some people are going to drive stupid anyway"

The recent accident involving the young cyclist Estela Domínguez brings the issue of cyclist safety on the road to the forefront once again. Drawing the line between what cyclists can do to ride safer and shifting the blame to the victims generates a debate on which not even those who ride bicycles can agree.

Minimizing risks on the road also depends on the cyclist

Reading certain comments on social networks, especially when the DGT makes some publication about the rules concerning cyclists, is usually a bit depressing if we go by many of the hateful comments about who pedals on the roads that can be read there.

The feeling remains that the road is a hostile place for cycling where it is little less than a suicidal act to pedal, especially if we add the social alarm that is created every time a more or less mediatic accident occurs, such as the one suffered a few months ago by Davide Rebellin or the sad death of the very young rider Estela Domínguez just a few days ago.

RECOMENDADO

Alcoholic beverages with the fewest calories

What would you do if you won the lottery? This cyclist bought himself a €20,000 bike

Tips for cycling in the rain

25 cycling gifts ideas to get it right

When do helmets have to be changed? Do they have an expiration date?

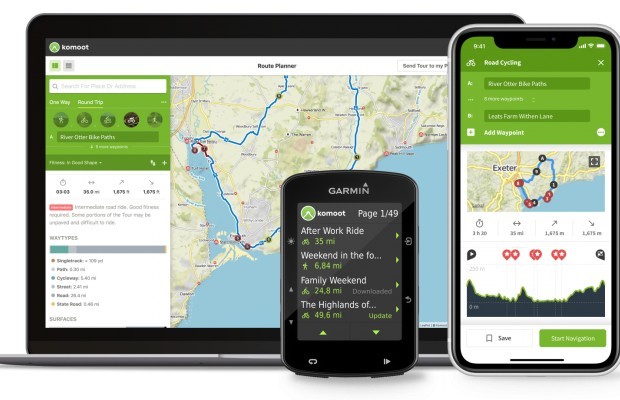

The best apps for cycling and mountain biking

In all these cases, the question always arises: what can we do to improve road safety? And often the recipes are the same: respect the rules, be visible, cycle on quiet roads, etc.

However, on many occasions, even from the cycling world itself, the blame for the accident is shifted to the cyclist himself, especially if the accident occurs at dawn or dusk in difficult lighting conditions or if the cyclist is wearing dark clothing.

It is true that one of the main safety recommendations is to be visible to other drivers, so that they can anticipate our presence as much as possible and be prepared to interact with us. In any case, it is not a foolproof recipe and we can always encounter the absent-minded driver, the driver who has consumed alcohol or drugs or, even worse, the reckless driver who still thinks that the road is his own private domain.

The quote in the title of this article is a good example of this last point, pronounced by Bob Donaldson, a cyclist of the Trinity Racing continental team, in whose structure Tom Pidcock was a member, who recently suffered a serious collision on a straight stretch with perfect visibility when a driver entered the road he was riding on without noticing his presence, The famous "I didn't see you" with which drivers often excuse themselves in many traffic incidents that, fortunately, in most cases are saved without consequences thanks to the skill of the cyclist. All this in spite of being equipped with lights and wearing the flashy clothing of his squad, designed in principle to favor visibility.

As we said, being visible is essential as a first measure of self-protection on the bike, however, we must be clear that 100% safety does not exist. In many cases, the focus has been placed on dark-colored kits, which many cyclists choose for their design and elegance, as opposed to bright or fluorescent-colored options that make us visible from a greater distance. However, the more visible garment alone only makes drivers aware of our distance, in low light conditions up to about 130 m away, a distance that a car traveling at 90 km/h covers in just 5.2 seconds.

The great innovation in terms of cyclist visibility came in 2015 when Trek launched its Bontrager Flare rear light designed, unlike the lights that existed on the market until then, to be used during the day, providing a visibility of up to 2 kilometers. It also improved the ability to see by providing a characteristic flashing pattern, two long flashes followed by three short flashes, making it unmistakable.

This multiplies the distance at which drivers can be aware of the presence of the cyclist, even long before even distinguishing his silhouette, and the intensity and flickering of these lights can attract attention even when the driver is distracted and takes his eyes off the road.

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

Such is the importance of the safety aspect of daytime running lights that even a cyclist of the stature of Tadej Pogacar, among many other professionals, has thrown his support behind the "Be Bright Wear a Light" campaign created by Australian cyclist Rachel Neyland of the Cofidis team.

Double-edged weapon

However, these campaigns promoting the active role of the cyclist in terms of safety are counterproductive for many, with the argument that they shift the responsibility in the event of an accident to the cyclist who was not wearing lights or was dressed in black.

They even point out that measures such as wearing lights do not improve protection and, on the contrary, may cause a false sense of security in the cyclist that makes them lower their guard while pedaling on the road.

These are, in fact, similar arguments to those put forward by the urban cycling world to reject the mandatory use of helmets, indicating that in the event of not wearing a helmet in an accident it can be used as an argument to blame the cyclist, without taking into account that wearing one or not makes little difference in the event of being hit by a car, but that its protection is almost solely oriented to the crashes that the cyclist may suffer.

Obviously, each accident is different and requires a detailed analysis to establish the causes. It is not always the drivers who are responsible for an accident, nor is it always the cyclist who is the reckless person who rides carelessly on the roads, even though there are still those who ride at night without lights or fail to comply with other types of rules.

Returning to the example of the Valladolid cyclist Estela Domínguez, the information we have been gathering leads us to conclude, completely unofficially, that the accident was caused by a concatenation of circumstances: sun glare from the front, a complicated point on the road with junctions on both sides, and the driver's distraction. In this case, nothing could have been done for Estela by the rear lights that, as some cyclists who rode with her told us, she always carried on her bike.

In any case, what is obvious is that, despite the inherent dangers that the road hides, we must be clear about the aspects that are in our hands, such as trying to be more visible, but also others such as respecting the rules, driving in a predictable way or preferring roads that avoid complications such as excessive traffic or points that expose us to drivers' mistakes.