How aero bikes have changed over the last decade

Looking back, today's aero bikes have little in common with those that dominated the catalogues 10 years ago. From being considered an almost exclusive feature of time trial or triathlon bikes, it has become a necessity for any road bike that is designed with competition in mind, like most brands' top of the range models, the same ones that the pros use in the world's best races.

The evolution of aero bikes

Before we begin to look at the evolution of aero bikes, it is necessary to point out how important this aspect has become in competition and performance oriented bikes. Traditionally, aerodynamics was only considered to a limited extent in time trials or beyond when everyone was aware of the power savings of riding behind other riders.

RECOMENDADO

When do helmets have to be changed? Do they have an expiration date?

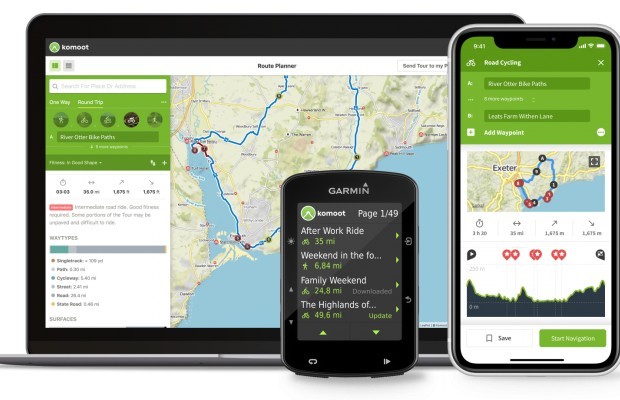

The best apps for cycling and mountain biking

Black Friday 2025 cycling bargains: save on Garmin, POC, Maxxis and more

Black Friday Garmin 2025: the ultimate guide to choosing your GPS at the best price

How to wash your cycling clothes? 10 keys to make them always look new

Cycling can help you fight the effects of the time switch

It was triathletes who first became aware of the possibilities for improvement on the bike offered by taking care of aerodynamics. In fact, it was from triathlon that the couplings for time trial bikes were born and made their spectacular appearance in the 1986 Tour de France, with Greg Lemmond overwhelming the field in the time trials and managing to turn the race around on the last stage by just 8 seconds.

However, aero bikes would remain almost exclusively a time trial thing, although they began to evolve into a truly surreal design that caused the UCI to take action and set rules for what an aero bike had to look like. However, conventional road bikes were still essentially just that, conventional bikes.

Perhaps we can say that the pioneers in introducing aero road bikes, at the end of the first decade of the century, were the Canadians from Cervélo, with those well-remembered Soloist bikes that later evolved into the S line that is still in use today. Other brands would follow the same trend, for example Canyon with its first Aeroad.

Constant evolution

The aerodynamics of bicycles basically consists of reducing the resistance they offer when passing through a fluid such as air. Wind resistance is the element that most opposes the cyclist's progress, growing exponentially as speed increases. It is considered that from about 15-20 km/h it begins to have a significant influence.

Within this resistance, 80% of it is up to the rider, which can be improved by better positioning on the bike or by wearing close-fitting clothing and other items such as helmets that offer a better wind profile.

The other 20%, a not insignificant figure, especially as it remains constant unlike the cyclist who can move, change position with fatigue, etc., is attributable to the bike. Although in many cases the gains obtained by improving the bike, especially in the case of road models, can be described as marginal because of their small influence, the sum of these benefits does make an appreciable difference: wheels, handlebars, frame, crankset... even the derailleur pulley box has been the target of the search for better aerodynamics.

Focusing on the frames themselves, the bike brands, at that time without much access to the technology and knowledge of the aeronautical world, began by opting for the basics: teardrop-shaped tubes that elongated towards a fine-tipped end. The longer the length of this aero profile, the greater the gain. It was as simple as that, with hardly any further studies to assess the improvements and the influence of each element. Otherwise, the general design lines of conventional bikes were maintained.

The downsides of aerodynamics

However, despite the performance gains that aero bikes could introduce, aerodynamics were not something that came free to designers.

The introduction of large aero profile tubes had a noticeable influence on the bike's behaviour. It's just a matter of physics. If you make very narrow and very elongated tubes, they are going to be more flexible laterally and very stiff lengthwise. Translated to the bike, this meant less lateral stiffness and a dry and not very absorbent feel, just the opposite of what you are looking for in a bike.

Also, adding aero profiles necessarily means more material, which in addition to the need to reinforce areas such as the bottom bracket to compensate for the aforementioned lack of stiffness, translates into an undeniable increase in weight. Furthermore, so much profile size in the direction of travel meant that the side wind played an important role and greatly affected the handling of these bikes.

The revolution

For all this, the development of aerodynamic bikes was not great, at least not beyond a mere aesthetic issue until 2012 when Scott launched its Foil model, a bike that boasted great aerodynamic qualities but avoided the limitations of traditional aero profiles.

Until that time the belief was based on airfoils derived from the world of aviation and the belief that the frontal section had to be reduced as much as possible. However, when the use of fluid dynamics simulation software and wind tunnel studies became standardised, engineers, some of whom came from the world of Formula 1 where aerodynamics is a fundamental part, began to find new ways.

To provide drag reduction there was not only the option of a long, slim profile, in fact, what was perfect for an aeroplane or a Formula1 did not work best on a bike moving at much lower speeds.

Aerodynamic drag occurs for various reasons. Broadly speaking, because of the frontal surface that the air has to pass through, because of the turbulence generated around it or because of the vacuum that is left behind the bike when the air is pushed away. The aerodynamic profile of the tubes means that instead of breaking the airflow, the air stays close to the surface of the tube, accelerating along the way and exiting and rejoining at the rear with as little turbulence as possible.

When Scott developed its Foil, they found that good performance could be obtained with a wider front end, something that Zipp had already popularised with its Firecrest wheels, as the shape of the profile was more important for the flow to stay close to the surface than the frontal area.

On the other hand, and more importantly, they found that by cutting the tail and leaving the trailing edge flat, the wind would still have the same path as if it existed. By doing this, they found a solution to the problems, as they could make wider tubes that would provide the necessary stiffness to the bike and yet not so long that they would make it an unrideable machine, both for lack of comfort and for the problems with side winds.

As always, when a solution works, it is immediately copied by others, so that more or less radical Aero-specific bikes began to appear in the ranges, although the limitations imposed by the UCI for competition bikes partly limited the imagination of the designers and prevented things from getting out of hand.

How bikes have changed

Even so, what in the first stage were bikes with a multi-purpose approach gradually evolved towards specific models in which new solutions were introduced to shave a few seconds off the time: integration of the stem and fork with the lines of the frame, seat stays anchored to the lower part of the seat tube, the rear part of the seat tube following the contour of the rear wheel, a widened diagonal tube to avoid the influence of the bottle cage or even small flaps on the legs of the fork, or totally internal wiring. Last but not least, the deflectors introduced by Bianchi on its new Oltre.

Some solutions work and end up staying, such as the low seat stays, common on almost all bikes on the market, not only for aerodynamics but also because they simplify frame construction by allowing the same rear moulds to be used for all sizes. Other solutions, whose contribution is minimal, end up disappearing as they do not represent an obvious improvement.

The last big change came a couple of years ago when the UCI relaxed the regulations for aero bikes, which required that the proportions between the height and width of the different tubes be maintained. This has allowed the brands to go much further and go back to using deeper profiles, although now, with the knowledge acquired, neither truncated rear ends nor more generous widths are no longer being abandoned in order to also adapt to today's increasingly bulky tyres, whose effect on air flow and interaction with the bike's tubes is also being taken into account.

In any case, the generalisation of aerodynamics in all bikes has also led to a curious involution, that of the so-called aero light, climbing bikes with aerodynamic qualities but not as radical as the more specific models. The most striking case is that of Specialized, which improved the aerodynamics of its Tarmac so much that it ended up opting to remove the Venge model from the catalogue as the climbing bike was almost as aerodynamic as the specific one and at the same time, much lighter.

Others, such as Trek, have kept both models in their catalogue, opting to provide the climber with good performance in the wind and, on the other hand, radicalising their aero bike, the Madone model, with lines that do not go unnoticed.

What is undeniable is that aerodynamic improvements are now commonplace on all bikes and that everyone can benefit from them to a greater or lesser extent. Obviously, the first thing is to get a good position on the bike and not to wear baggy clothes. After that, the bike will always be there to do its bit.